How to Stop Thinking a Thought

How does someone, anyone, stop thinking a thought that he or she does not want to think?

I am referring to a vexing frustration. Or a fear. Or a sense of having been slighted or belittled by another. A regret over something that can’t be changed. A cringe; a temptation down a fruitless path; a comparison with someone else who seems better off in some way. A worry. I am referring to any of the many lines of thought that haunt our minds and rob us of peace, raising emotion we would rather not feel or urging action we are better off not taking.

This question is one of the most pressing we face for navigating life and tacking toward happiness as best we can. Sadness or suffering sometimes directly comes from events we cannot control or the circumstances we find ourselves in. Yet in many other cases, sadness or suffering is less about events or circumstances, and more about the premises or habits of thought we allow to take over our thinking.

But even here—look what I just did—I am already oversimplifying the matter. At the end of the preceding paragraph, I spoke of what we “allow” thoughts to do, as though we grant permission, as though we could simply withhold the permission and thereby fix the problem. Is that true? Is that a useful premise? As everyone knows who has ever lived with a thinking mind, controlling the mind is not so easy.

Thus, I do not entirely know, nor even mostly know, how to stop thinking a thought I do not want. Direct tactics are self-defeating. Determining that I will do X to stop thinking Y means I must draw very close to thinking Y just to formulate this tactic. Resistance really is futile. But the matter is not hopeless. On some level, our thoughts do provide a setting in which we can engineer different and better thoughts, our mental state in a sense bootstrapping itself. How?

Again, I do not know, not entirely. If there was a meditation that would set my mind right, I would do it. Instead, I am apt to sometimes find myself, say, sleepless with troubledness, or pacing with anger, neither of which does anyone, least of all me, any good. So how do I unthink or not think the thoughts that feed these emotions? At best I see pieces of the answer, so this article will unfortunately go only that far and no farther.

How can a mind avoid or evade an unwelcome or unhelpful thought? What follows are portions or fragments. Here are some clues. All of this is true as far as it goes:

1. Tiredness matters

Reason requires will, and will requires mental effort. Thinking takes energy. The mind and brain get tired. This is at one level obvious, and at another level it is difficult to see.

Indeed, the mind can get deeply tired, just as the body does. But because we each live at the center of the mind through every moment, at the center of the self through every moment, we cannot necessarily gauge the self’s responses and capacities as they change from one moment to the next. Unreason washes over me sometimes simply because my reason is too weak to hold it back, and I need to see this.

In fact, the analogy to physical tiredness breaks down only because this analogy does not go far enough. If my body is too tired to carry a weight, I will feel and experience how hard it is to carry the weight. But recognizing that my reasoning is tired is itself an act of reason. In mental tiredness, I am mentally less inclined to recognize how tired I am.

One of the tactics for not thinking a thought, therefore, is to acknowledge in advance that tiredness is a factor. Carry the simple truth that a rested mind will see more clearly, and will more readily trust in thoughts that are positive and hopeful, than a mind that is weary. Look at this simple truth often and check thoughts against it at different times of day. Many of us are weary much of the time, so this simple truth is apt to see frequent use. When darkness pours in, remember that there is a stronger, better, more capable version of this same self who will have enough light of reason to reveal a clearer view of the same situation. The better self, the clearer mind, is probably just one sleep away.

2. There is a quick chance to turn away

The harmful thoughts that rob us of peace or joy, centering on stresses we would rather not worry over or slights we would do better to ignore, are thoughts other than the inklings that flash across the mind in an instant. The harmful thoughts are the ones we take hold of and turn over and over again. A sense of fascination figures in: This thought gives me fear or hurt or anger—just how deep or sharp is it, how far does it go? Our darker thoughts are thus obsessive to an extent, and the obsessing has a mental momentum that is hard to stop. The easiest time to turn away is in the moment before the turning over and over begins, before the rehearsal and repetition of the line of thinking is fully underway.

It is possible to see this early moment. As intimate as we are with our own minds, none of us knows how thoughts begin, where they come from. I do not seem to be choosing which thoughts come to my mind. Rather, our thoughts appear. They arrive. And when they do, there is a moment of agreeing with a thought, of picking it up. This act is, to an extent, optional. I can disagree rather than agree in this moment. To do so is an act of will, and like any act, there is a decisiveness to it that can feel like a stern push.

“Whoa!” I might say or ought to say, within my mind, when I see the first suggestion of a thought that is no good to pursue. “No way am I picking that up!”

Like a live wire, I leave the thought untouched. Like a downed power line, I can see it sparking and dancing even as I back away and demur to touch.

To get free, I often announce to God my intention to not accept that thought. I ask him to provide something else to think about instead. Escape in this moment, when it happens, can be quick and sure.

Escape is also possible later, if I have picked up the line and its currents now course through me. Letting go is harder here, so a different tactic is needed.

3. Outer action shapes inner experience

The life we know and remember is built through actions, events, and experiences that happen on the outside, not in our minds. Think about this and you might agree it is true.

This is not our intuition. That is, this outwardness about the way life is known and lived does not seem to be the case in any present moment in which we are living. “Within” is where we seem to be living instead. The brush with which we are painting life seems to be applying its strokes inside, in our minds, in our feelings, for better or worse. However, the color that lasts is on the outside.

I see this, for example, in my memories of vacations. A vacation is a special time in which my family and I leave work and school, and travel to briefly enjoy a different place. And on every vacation, I take myself with me, of course—my “self,” with all its anxieties and burdens. I leave work and leave my daily life for vacation, but not really, not completely. Generally, my thoughts are rolling over some problem or incompleteness out of daily life that I might need to face, address, or solve when I return. But here is the thing: When I look back on vacations of previous years, I only remember the things I did, or outwardly experienced. Even if I was concerned or distraught about something, I generally do not remember the feeling of concern or distress, and do not remember whatever the issue was that was the center of those feelings at the time. That is, what I experienced internally does not leave a mark, if the experience was entirely internal. I only remember if I took an external action. That is, if I sent an email or took a call in response to the situation. If I did this, then that action imprints a lasting mark, so that in this case I do remember both the action and the concern around it. But outer action like this is needed, or else the inner turmoil passes without having a lasting effect.

That preceding paragraph was a lot, but here is what I see in this observation about internal versus external experience: I see the grounds upon which to deny an unwelcome thought, or turn it away. I can do this by taking action. That is what I should do: Take action—just not the action the thought is urging. Instead, I can go for a walk, fold laundry, run an errand. What the dark or petty thought “wants,” if it can be said to want something, is to spread its darkness or pettiness by leaving a mark that lasts in the form of some step or action in the outside world. Even a little concession, like repeatedly checking something in response to an irrational concern, is an action that can leave an outer mark in memory, time, and attention spent. But taking a productive action in place of the action the thought wants is a way to deny that thought, and do so to such an extent that memories of the future might not even make a record of the concern.

4. “Whatever” makes a life

With all these types of thoughts we are considering—worries, resentments, regrets—the principal thing they ask of us, the condition they ask us to accept, is that they be taken seriously. The thought is not necessarily or inherently grave, but rather it is weighty because we make it so with the gravity of our consideration. In a separate light, the same thought might be seen as ridiculous.

Against this weight that our thinking gives to a thought, the airiness of a different, positive course of thought might seem to be unrealistic. After all, we imagine, the serious thinker gives serious weight to a serious concern—not able to see how we made the concern serious with the force of our own attention. There needs to be a way to change the framing so that peace and happiness can be the serious matter instead.

“Whatever” is that way. Whatever: the adverb of graceful escape.

In the outer world of action and choice, we tend to fault those who have an attitude of ambivalence, perhaps rightly so. But in the inner world where thoughts grow, loom, and seem to be compelling, “whatever” can be the slipping of the trap, the sidestepping to a more peaceful place. Whatever you seem to be saying to me, Negative Thought, I do not care because hopeful and positive thoughts are better—even if I have to pretend to be hopeful and positive until the seriousness of the shadow of resentment or temptation passes.

I began this essay with the recognition of how difficult it is to release or unthink a negative thought, but doing so is not impossible. Among the distortions these thoughts produce is the feeling that the mind, the inner experience, is crowded and cramped. In fact, it is spacious. If we believe this inner space is touched by the eternal, it is infinite. “Whatever” is a tactic that works, when it does, because it leverages the abundance of open space to allow for better thinking to form. In our minds, in this inner realm, particularly if we know or look for the divine, we need never be lacking for a better and higher place on which to make a stand.

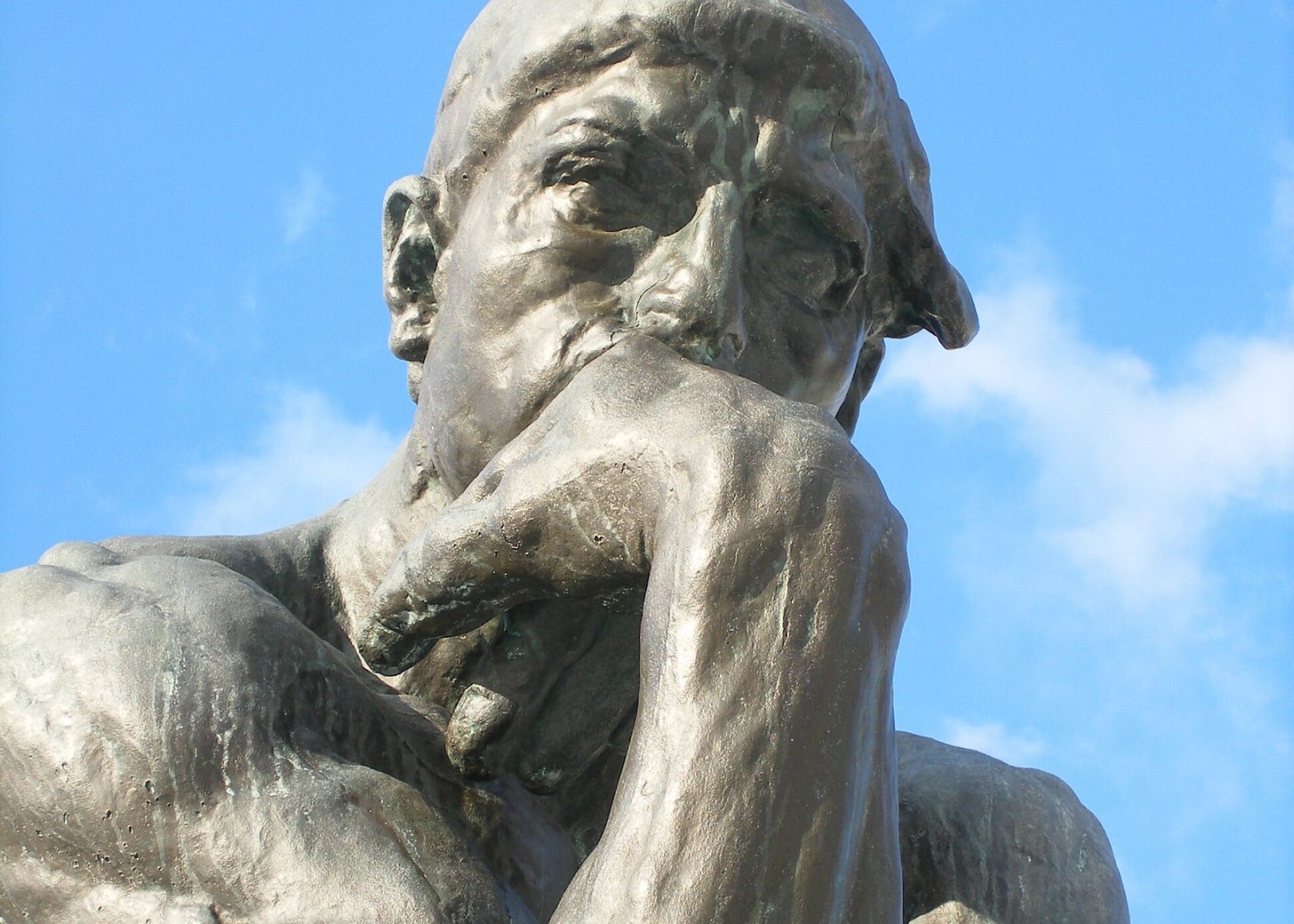

Photo: “Think” by Brian Siewiorek